The unfolding events in Gaza have brought the Arab-Israeli conflict back to the forefront of regional and international politics. Analyses have so far focused on the capacity of Hamas to execute its terrorist attack on 7 Octoberi, the possibility of a regional war with the participation of Iran and its proxiesii, the humanitarian cost and its legal implicationsiii, the IDF and Hamas’ strategies and the way forward in terms of conflict resolution.iv

This report focuses on the interplay of the conflict with domestic political crises in Middle Eastern states and the regional implications of this interplay. Since the Arab Spring uprisings in 2010, the Arab-Israeli conflict, once seen as the defining characteristic of Middle East international relations, has fallen down the pecking order of regional issues. Instead, the regional and domestic implications of the Arab Spring, along with the antagonism between Saudi Arabia and Iran, have received the lion’s share of attention. Nonetheless, the Arab-Israeli conflict has continued to be seen as an essential issue by Arabs across the region.v

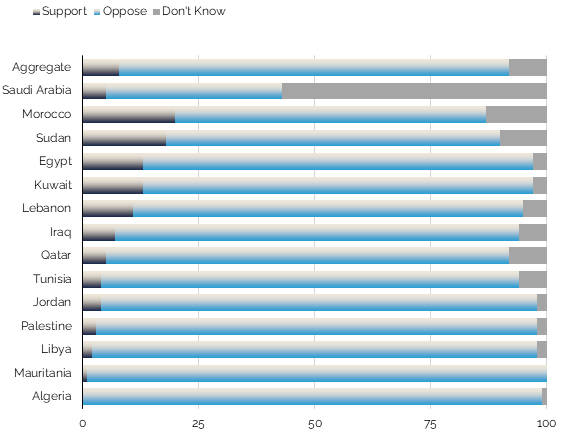

Recent polling has shown that the majority of citizens in Arab countries oppose the ongoing normalisation between certain Arab states and Israel, with Arabs continuing to view the Palestinian cause as important. The results illustrated in the graphs below are the result of the 2022 Arab opinion Index conducted by the Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies in Doha. The survey took place in 14 countries and 33,300 people were intereviewed, making it by far the most extensive research in the Arab World.

Exhibit 1: Support for normalisation between Arab states and Israel

The events since 7 October have brought the Arab-Israeli conflict back to the forefront of Middle East and global politics. On a domestic level, Arabs across the region have demonstrated renewed support for the Palestinian cause.vi Popular mobilisation against Israel may become a source of instability for regional governments that have struggled with important socioeconomic challenges in recent years. These dynamics occur against the background of a wider region that had been engulfed in conflict long before the onset of hostilities in Gaza and Israel. The two long-standing conflicts in Syria and Libya are ongoing, albeit at a toned rate.vii Meanwhile, the war in Yemen continues, while another conflagration in Sudan has been added to this long list of wars in the Middle East and the Arab World.

This report emphasises how the latest round of fighting in Gaza is likely to affect the domestic political scene in many Arab states and thus further destabilise the region. It does so by focusing on three states: Lebanon, Jordan and Egypt. The war affects these three states directly due to their geographical proximity to the conflict. All three states have historically played a vital role in the Arab-Israeli conflict. Moreover, all three face prolonged social and economic crises. In this respect, the war is likely to destabilise them even further. The report considers each of the three in turn.

Lebanon

The economic and political position of Lebanon has been dire for some time now. The country has recently been experiencing its worst political and socioeconomic situation since the end of the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990), facing multiple parallel crises. It is in a political stalemate since Michel Aoun’s presidency ended in October 2022, with no majority in the Lebanese parliament for the election of a new president.viii This is not a new phenomenon, with Lebanese politics hampered by a confessional governmental system of cross-sectarian alliances, antagonisms, and rivalries within sects.

The existence of cross-sectarian alliances within the current caretaker government and the dominant ‘8 March’ alliance, the country’s leading political bloc, illustrates how contemporary Lebanese politics do not resemble the picture of rigid sectarianism often painted by analysts.ix Sectarianism still matters, however, because it has allowed external actors to play a role in the country’s political scene since the country’s independence in 1943. Iran, Saudi Arabia and France have battled for influence in Lebanon, adding another source of instability to an already complex political scene.x

Economically, the country is in its worst condition since the end of the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990). The Syrian Civil War, leading to inward refugee flows of approximately 1.5 million people, has affected Lebanon’s weak institutional capacity and hurt the tourist industry, a key pillar of the economy.xi By 2019, the Lebanese state had defaulted on its debt, meaning it could not refinance its debt through international lending. The capital controls imposed on banks led to the latest in several rounds of wealthy Lebanese seeking to shift their assets and businesses abroad. The Lebanese pound has rapidly devalued while the percentage of the population living in poverty has surpassed 50%.xii Simultaneously, the COVID-19 pandemic pushed the national health services to their limits.

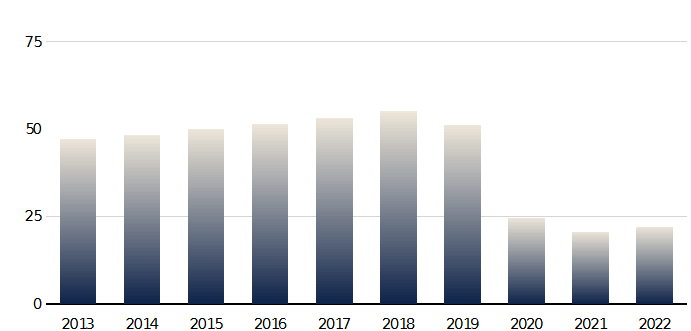

In 2020, the situation turned from difficult to dire with the explosion of an ammonium nitrate cargo in the port of Beirut, leading to 218 deaths, 7,000 injuries, and 15 billion USD in property damage. In its immediate aftermath, 300,000 people lost their homes.xiii According to the IMF, the economic shock was resounding, with Lebanon’s GDP plummeting from approximately 53 billion USD in 2019 to 20.48 billion USD in 2022.xiv The percentage of the population living in poverty currently exceeds 80%, with about 30% of the population living in extreme poverty.xv

Exhibit 2: GDP in Lebanon (per billion US dollars)

The latest conflict in Gaza is likely to worsen the situation in Lebanon yet further. Much rests on whether Hezbollah will escalate its involvement in the conflict. Hezbollah, a Shia Muslim party, is characterised as a terrorist organisation by most Western actors.xvi An Iranian proxy, it boasts a military wing more capable than that of Hamas. Hezbollah fought against Israel with relative success in the 2006 conflict that ended Israel’s occupation of southern Lebanon. So far, Hezbollah has kept its involvement limited, although hostilities have picked up after its leader, Hassan Nasrallah, addressed the public for the first time on 4 November since the onset of hostilities in Gaza on October 7th.

Lebanon’s fate hangs in the balance and depends on the response of Hezbollah to the conflict. As the most potent Iranian proxy in the Middle East, the Hezbollah leadership has felt pressure to escalate its involvement. Hezbollah’s legitimacy rests on a narrative that positions it as the leading force in “the resistance against Israel”.xvii With a large percentage of Lebanon’s Sunni community descending from Palestinian refugees – numbering approximately 250,000 – who fled the 1948 conflict, a Hezbollah intervention has garnered broader popular backing among Lebanese Muslims.xviii

On the contrary, Hezbollah’s political opponents within Lebanon have urged the group to refrain from further escalation, fearing it would prompt the IDF to attack Hezbollah positions in southern Lebanon.xix A spillover of the conflict in South Lebanon would cripple the country’s economy and infrastructure, potentially leading to sectarian conflict, especially should Israel seek to exploit Lebanon’s sectarian cleavages, inciting rival groups against Hezbollah. Finally, an escalation by Hezbollah would signify the transformation of the conflict into a truly regional war, propelling Lebanon into further chaos with likely severe humanitarian consequences.xx

Jordan

The social and economic challenges of Jordan, which borders Israel to the east, are less severe than those of Lebanon, but nonetheless remain critical. The roots of its recent economic problems lie in three domains. First, the civil war in neighbouring Syria led more than 650,000 refugees to seek shelter in Jordan since 2011, putting further pressure on a state with weak institutional capacity. Second, to avoid a default on its debt, the Jordanian government was forced to seek a comprehensive IMF support package in 2016 to the tune of $732 million with a second package being approved in 2020 worth $1.3 billion. The packages agreed involved austerity measures, limiting the capacity of the government to tackle a growing cost of living crisis. Despite the introduction of the IMF program, key economic indicators have deteriorated, including the debt-to-GDP ratio, which is now higher compared to the period before the IMF-led measure. Meanwhile, the level of poverty rose from 15%-24% between 2018 and 2022.xxi Third, Jordan has chronic problems related to the quality of its governance, with corruption a key concern. The austerity and the cost-of-living crisis sparked major protests in 2018 and 2022. The protests focused on bread and milk prices, with riots in December 2022 leading to the deaths of several police officers.xxii

These prolonged difficulties have shaken trust in the government and the Jordanian ruling monarchy. While the position of the Hashemite dynasty is not immediately threatened, the conflict in Gaza will undoubtedly put pressure on the government to take a tougher stance against Israel. Jordan has had diplomatic relations with Israel since the Oslo negotiations in 1994, and has been touted as a possible diplomatic broker in the Arab-Israeli conflict. As the conflict continues and pressure mounts on the government to take action, initiatives like the multilateral summits in which King Abdullah took part are unlikely to help the government avoid public scrutiny. Jordan is home to an even large number – two million – of Palestinian refugees from the 1948 and 1967 conflicts than Lebanon, something which contributes to pressure for a tougher Jordanian stance against Israel. There are concerns this could translate into a severing of diplomatic ties, which would set the regional peace process back by decades.

Jordan will face important economic challenges depending on how the conflict develops. The escalation of the conflict in the West Bank could potentially lead to new refugee flows, burdening an already weak Jordanian economy.xxiii Indeed, this is a danger that the markets have acknowledged, with a surge of almost 1% in Jordan’s 2030 dollar-denominated bond during the first week of the conflict.xxiv Ultimately, a prolonged conflict would result in even higher borrowing costs. Lastly, the Jordanian economy is heavily reliant on its tourism sector, responsible for approximately 10% of the country’s GDP. The onset of hostilities in the Middle East will reduce the attractiveness of Jordan as a tourist destination, no doubt stymying a valuable source of national income.xxv

As a result, massive protests have been sparked in response to the rising death toll in Gaza, putting pressure on the government to take a stronger stance against Israel.xxvi So far, the government’s response was to recall its ambassador from Israel on 1 November due to the “unprecedented humanitarian catastrophe” and the killing of innocent people in Gaza”.xxvii Jordanian diplomacy has been active by engaging with other Arab and Muslim states while the kingdom has also engaged with Western states. However, if the conflict is prolonged in light of the socioeconomic crisis facing Jordan, the Hashemite dynasty will undoubtedly face challenges to its rule and its legitimacy.

Egypt

By virtue of history, geography and size, Egypt is likely to play an important role in the unfolding conflict. Historically, Egypt is a regional power in the Middle East and the Arab World, and a critical actor in the Arab-Israeli conflict. The normalisation of relations with Israel in 1979 signalled a key turning point in the conflict, with Egypt no longer willing to provide military aid to the Palestinians following the Yom Kippur War in 1973. Geographically, Egypt is the only state, other than Israel, that borders Gaza and has played a role in its blockade. The Rafah border crossing between Egypt and Gaza is of critical importance since it is the only entry point for much-needed humanitarian aid, and a key corridor for the evacuation of foreign nationals trapped in Gaza.

Like Lebanese and Jordanian actors, the Egyptian government has had to carefully calculate its response to the latest conflict. Egypt has struggled financially since the restoration of military rule under General Fatah al-Sisi in 2013. The country has requested external support to remain afloat, becoming Africa’s largest ever IMF loan recipient. It has also relied on loans and aid from Gulf states.xxviii The IMF has called upon Egypt to enact reforms focused on privatising state assets, which would mean lessening the army’s grip on the economy. However, actors within the government have pushed back, complicating Egypt’s dealings with the IMF.

Another point of contention between Egypt and its key borrower concerns monetary policy. The Egyptian lira has been devalued three times since 2022, with the IMF’s chief, Kristalina Georgieva, arguing that another devaluation is required, much to the consternation of the Egyptian government.xxix This devaluation is being called for following the presidential elections of December 2023.

The conflict in Gaza serves further to complicate this unstable fiscal and monetary situation. International borrowing markets and rating agencies have not taken lightly the prospect of an all-out regional war or a refugee outflow from Gaza into Egypt.xxx Fitch, Moody, and Standard and Poor have downgraded the Egyptian economy to ‘junk’ status, citing external financing needs, increasing debt, and the poor investment of borrowed money.xxxi Egypt is likely ‘too big to fail’, but the reality remains that its ability to finance its debt and other financial obligations will significantly deteriorate.xxxii

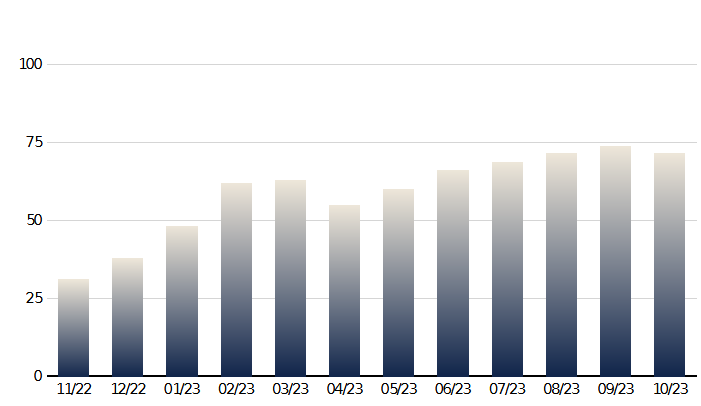

The economic situation is even worse for the average Egyptian. Egypt is engulfed in an unprecedented cost of living crisis fuelled by high inflation caused by currency devaluation and the effects of the war in Ukraine on food imports. In September, the annual urban consumer price inflation rose to an all-time high of 38%.xxxiii Food inflation has been even worse, peaking at 73.6% in September 2023 before dropping to 71.3% in October.xxxiv The government seeks to address this challenge in the medium and long term by investing in advanced technology projects that will enable increased agricultural production, a need made all the more imperative by the country’s growing water scarcity issues.xxxv But currently, Egypt is heavily reliant on food imports, which have come under stress since the onset of the Russo-Ukrainian war, putting the country in a precarious position.xxxvi

Exhibit 3: Food Inflation in Egypt

The picture for Egypt is a difficult one, and the conflict in Gaza looks set complicate it even further. The government has tried to mobilise public sentiment in its favour through state-sanctioned protests supporting the Palestinian cause.xxxvii One should remember that protests in the country are banned. However, non-state-sanctioned protests have sparked in recent weeks. As the death toll in Gaza rises, there will be pressure on the Egyptian government to take a more confrontational stance against Israel. So far, the Egyptian government has shied away from such a stance. Instead, its efforts have focused on coordinating Arab responses to the conflict through multilateral summits, while utilising the Rafah border crossing for humanitarian aid and evacuation of foreign nationals. Along with Qatar, Egyptian officials have been involved in back-channel diplomacy, mediating between Hamas and Israel for the release of hostages, with the recent truce partly a product of Egyptian diplomacy.

However, the Egyptian government will be called upon to make difficult choices as societal pressures build up due to the conflict and the prolonged economic crisis. It is not beyond the realm of imagination that these two factors could spark widespread protests with social and political demands shaking the government’s hold on power. At that point, one option for the Egyptian government is to take a tougher stance against Israel, taking measures such as the severance of diplomatic ties to satsify growing public demand. The second would be to try and weather the storm, conscious that a more aggressive stance on Israel could create friction in the country’s relationship with the US, key European states, and the IMF.

Conclusion: Domestic Crises and Regional Implications

The domestic crises in Lebanon, Jordan and Egypt are likely to deteriorate further as a result of the conflict in Gaza. In Lebanon, Hezbollah remains the key player, and its involvement in the conflict will determine its expansion into southern Lebanon, which appears certain to overwhelm Lebanon’s already weak institutions and public infrastructure. In such a scenario, the possibility of civil strife within Lebanon would increase, as would the risk of drawing in external actors. Jordan is in a precarious financial position, relying on IMF loans to remain afloat. The conflict will undoubtedly affect the all-important tourist industry and, should hostilities spread into the West Bank, new refugee flows will likely provide another humanitarian challenge to the government. As the protests of the past five years have shown, public trust in the government is at a low ebb, and the conflict can spark a new round of protests that could eventuate in political challenges to the monarchy. A similar situation exists in Egypt, where the country is faced with an economic and cost of living crisis. Notably, the conflict has led to several small non-sanctioned protests since 7 October. This represents a challenge to the government with the possibility for further public mobilisation sparked by the conflict.

Internal instability, particularly in Egypt and Jordan, may contribute to unraveling the limited security architecture of the region. If the ruling regimes of both Egypt and Jordan are moved by public outcry and mass mobilisation, they are likely to take a tougher stance on Israel. This would not lead to their direct participation in the conflict, but could result in a rapid decline in diplomatic relations. Under such a scenario, the US-led process of normalising relations between Arab states and Israel, which began with the 1979 Camp David Accords and led most recently to the Abraham Accords, could be stalled, or partially unravelled. With this in mind, international policymakers will be required to pay attention to the internal dynamics of regional states and not just to events in Gaza. In so doing, they will likely be compelled to work with local authorities and actors to promote conflict resolution. As shown by rigorous polling, the Arab-Israeli conflict remains, for the citizens of regional states, an issue of paramount importance, with the ongoing normalisation of relations between Arab states and Israel largely unpopular. This is a trend which predates the conflict that erupted on 7 October.1 Such sentiments are likely to be amplified by events unfolding since, and to be increasingly on the agenda of international policy makers over coming weeks and months.

i Joe Macaron, “Analysis: Why did Hamas attack now and what is next?,” Al-Jazeera (11 October 2023). https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2023/10/11/analysis-why-did-hamas-attack-now-and-what-is-next; Shira Rubin and Loveday Morris, “How Hamas broke through Israel’s border defenses during Oct. 7 attack,” Washington Post (27 October 2023). https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2023/10/27/hamas-attack-israel-october-7-hostages/.

ii Patrick Wintour, “How Iran uses proxy forces across the region to strike Israel and US,” The Guardian (2023), https://www.theguardian.com/global/2023/nov/01/how-iran-uses-proxy-forces-across-the-region-to-strike-israel-and-us. Alex Vatanka, “Iran Can’t Afford a Regional War,” Foreign Policy (2 November 2023 2023). https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/11/02/iran-regional-war-israel-hamas-hezbollah/.

iii David J. Scheffer, “What International Law Has to Say About the Israel-Hamas War,” Council on Foreign Relations (19 October 2023). https://www.cfr.org/article/what-international-law-has-say-about-israel-hamas-war#:~:text=The%20state%20of%20Palestine%20also,Israeli%20territory%20or%20in%20Gaza.

iv Matt Spetalnick and Alexander Cornwell Samia Nakhoul, “What is Israel’s endgame in Gaza invasion?,” Reuters (19 October 2023). https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/israels-endgame-no-sign-post-war-plan-gaza-2023-10-18/; Joseph Krauss, “What was Hamas thinking? For over three decades, it has had the same brutal idea of victory,” Associated Press (12 October 2023). https://apnews.com/article/israel-palestinians-hamas-conflict-endgame-1bfcc187d826596e78090ec6cbf6516c.

v Arab Center Washington DC, “Arab Opinion Index 2022: Executive Summary,” Arab Center Washington DC (19 Januray 2023). https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/arab-opinion-index-2022-executive-summary/.

vi Sam Jones, “Angry protests flare up across Middle East after Gaza hospital blast,” The Guardian (18 October 2023). https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/oct/18/gaza-hospital-al-ahli-al-arabi-blast-explosion-protests-demonstrations-middle-east.

vii For an up-to-date analysis of the conflicts in Syria and Libya see “Syrian Civil War’s Never-Ending Endgame,” World Politics Review, updated 3 November, 2023, accessed 1 December, 2023, https://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/the-syria-civil-war-might-be-ending-but-the-crisis-will-live-on/; “Civil Conflict in Libya,” Council on Foreign Relations, 2023, accessed 1 December, 2023, https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/civil-war-libya.

viii Per the provisions of the Lebanese constitution an individual needs a two thirds majority to be elected President. By convention, the Lebanese President comes from the country’s Christian Maronite community. On the Lebanese constitution and sectarian politics see Paul Salem, “Framing post‐war Lebanon: Perspectives on the constitution and the structure of power,” Mediterranean Politics 3, no. 1 (1998); Jeffrey G Karam, “Beyond sectarianism: understanding Lebanese politics through a cross-sectarian lens,” Middle East Brief 1, no. 107 (2017).

ix Karam, “Beyond sectarianism: understanding Lebanese politics through a cross-sectarian lens.”

x Stephanie T Williams, “Can the Saudi-Iranian rapprochement help address Lebanon’s governance crisis?,” (2023).

xi Ibrahim Yasin, “The Syrian Refugee Crisis in Lebanon: Between Political Incitement and International Law,” Arab Center Washington DC (3 October 2023). https://arabcenterdc.org/resource/the-syrian-refugee-crisis-in-lebanon-between-political-incitement-and-international-law/#:~:text=Lebanon%20is%20host%20to%20the,Commission%20for%20Refugees%20(UNHCR).

xii Dalal Mawad, “The aftermath: how the Beirut explosion has left scars on an already broken Lebanon,” The Guardian (3 August 2023). https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/aug/03/port-of-beirut-explosion-aftermath-scars-on-already-broken-lebanon.

xiii Mawad, “The aftermath: how the Beirut explosion has left scars on an already broken Lebanon.”

xiv IMF. “Lebanon: Gross domestic product (GDP) in current prices from 1987 to 2022 (in billion U.S. dollars).” Chart. October 10, 2023. Statista. Accessed December 01, 2023. https://www.statista.com/statistics/455250/gross-domestic-product-gdp-in-lebanon/

xv “Lebanon: €60 million in humanitarian aid for the most vulnerable,” European Commission (30 March 2023). https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/news/lebanon-eu60-million-humanitarian-aid-most-vulnerable-2023-03-30_en#:~:text=Currently%20around%20four%20million%20people,cannot%20cover%20their%20basic%20needs.

xvi For an overview of Hezbollah’s role in the conflict and its history see Jeffrey Feltman and Kevin Huggard, “On Hezbollah, Lebanon, and the risk of escalation,” Brookings (17 November 2023). https://www.brookings.edu/articles/on-hezbollah-lebanon-and-the-risk-of-escalation/.

xvii Huggard, “On Hezbollah, Lebanon, and the risk of escalation.”

xviii Mat Nashed, “Palestinians in Lebanon disappointed that Hezbollah won’t escalate,” Al-Jazeera (12 November 2023). https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2023/11/12/palestinians-in-lebanon-disappointed-that-hezbollah-wont-escalate?traffic_source=KeepReading.

xix Laila Bassam and Tom Perry, “Broken Lebanon cannot afford war between Hezbollah and Israel,” Reuters (27 October 2023). https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/broken-lebanon-cannot-afford-war-hezbollah-knows-it-2023-10-26/.

xx One could argue that we are already witnessing a regional war given that Hezbollah, the Houthi rebels in Yemen and the USA have been involved in the conflict. Nonetheless, the involvement remains relatively limited relative to the prospect of an all-out conflict which would see at least Hezbollah mobilizing its full force against Israel and the conflict expanding to southern Lebanon.

xxi “IMF: Austerity Loan Conditions Risk Undermining Rights,” Human Rights Watch (25 September 2023). https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/09/25/imf-austerity-loan-conditions-risk-undermining-rights.

xxii Laure Stephan, “In Jordan, anger at government mounts over rising cost of living,” Le Monde (19 December 2022). https://www.lemonde.fr/en/international/article/2022/12/19/in-jordan-anger-at-government-mounts-over-rising-cost-of-living_6008332_4.html.

xxiii “Jordanian PM rejects demands to scrap tax law after protests,” Reuters, updated 2 June 2018, 2018, accessed 20 June, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-jordan-economy-protests-idUKKCN1IY0S6.

xxiv Mary McDougall, “Israel-Hamas war sends jitters through neighbours’ debt markets,” Financial Times (15 October 2023). https://www.ft.com/content/d9871d2e-97d8-48ad-948d-f9ed5247a067.

xxv Laure Stephan, “Tourists are back in Jordan,” Le Monde (20 May 2023). https://www.lemonde.fr/en/economy/article/2023/05/20/tourism-returns-to-jordan_6027317_19.html#:~:text=The%20tourism%20sector%20accounts%20for,increase%20in%20revenue%20for%202023.

xxvi Marta Vidal, “Jordan’s Teetering Balancing Act,” Foreign Policy (2023). https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/11/30/jordan-protests-palestinians-gaza-israel-bombardment-war/.

xxvii “Jordan recalls ambassador to Israel to protest Gaza ‘catastrophe’,” Al-Jazeera (1 November 2023). https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/11/1/jordan-recalls-ambassador-to-israel-to-protest-gaza-catastrophe.

xxviii Ricardo Fabiani and Michael Wahid Hanna, “Egypt in the Balance?,” International Crisis Group (31 May 2023). https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/north-africa/egypt/eygpt-in-the-balance.

xxix Hanna, “Egypt in the Balance?.”

xxx McDougall, “Israel-Hamas war sends jitters through neighbours’ debt markets.”

xxxi “Fitch downgrades Egypt one notch deeper into junk territory,” Reuters (3 November 2023). https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/fitch-downgrades-egypt-b-with-stable-outlook-2023-11-03/.

xxxii Netty Idayu Ismail, “Citigroup Sees Egypt’s Clout in Funding Talks Boosting Bonds,” Bloomberg (26 October 2023). https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-10-26/citigroup-sees-egypt-s-clout-in-funding-talks-boosting-bonds?embedded-checkout=true.

xxxiii “Egypt’s inflation quickens to record 38% in September,” Reuters (10 October 2023). https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/egypts-inflation-quickens-record-380-september-2023-10-10/.

xxxiv “Egypt Food Inflation,” Trading Economics (2023). https://tradingeconomics.com/egypt/food-inflation#:~:text=Cost%20of%20food%20in%20Egypt,source%3A%20CAPMAS%2C%20Egypt.

xxxv Michaël Tanchum, “The Russia-Ukraine war forces Egypt to face the need to feed itself: Infrastructure, international partnerships, and agritech can provide the solutions,” Middle East Institute (25 July 2023). https://mei.edu/publications/russia-ukraine-war-forces-egypt-face-need-feed-itself-infrastructure-international#:~:text=Egypt’s%20agrifood%20production%20cannot%20meet,worsens%20its%20extreme%20water%20scarcity.

xxxvi Tanchum, “The Russia-Ukraine war forces Egypt to face the need to feed itself: Infrastructure, international partnerships, and agritech can provide the solutions.”

xxxvii “Angry Egyptians denounce staged pro-Palestine rallies amid Israel-Hamas war,” Al-Jazeera (21 October 2023). https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2023/10/21/exploiting-our-anger-egyptians-denounce-staged-pro-palestine-protests.