Europe faces a critical juncture. Most indicators suggest the continent is falling behind its peers in strategic technology. Leveraging trade and FDI for technology transfer is a prospect leaders are taking increasingly seriously.

Summary

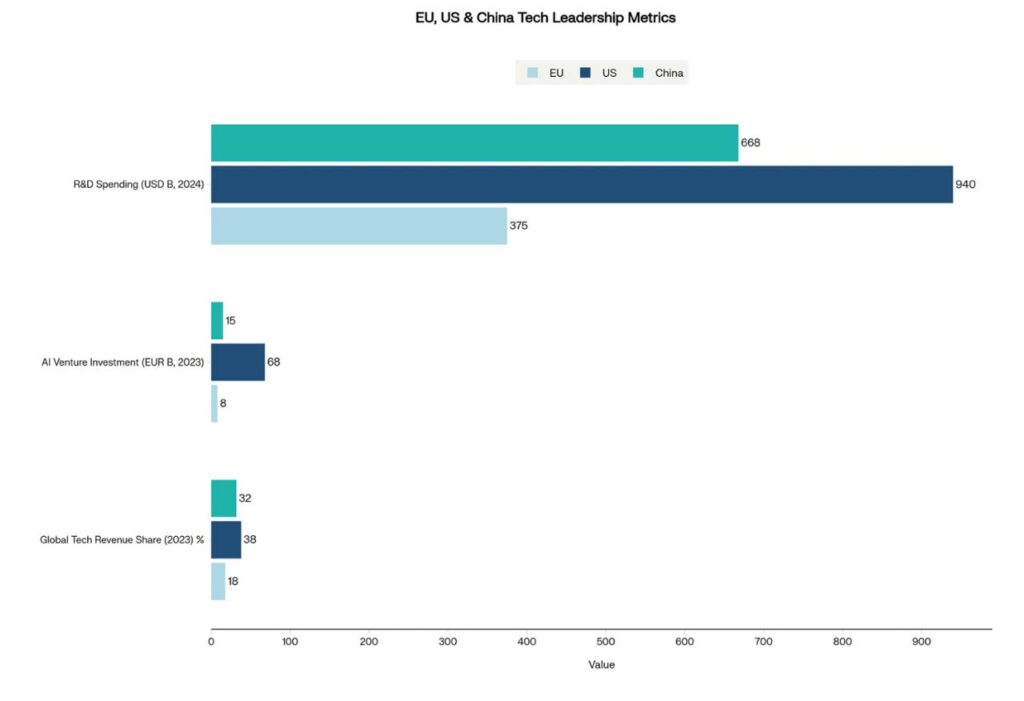

Europe stands at a critical juncture in the global technology landscape. While historically a leader in innovation, the continent has fallen behind the US and China, and faces significant challenges in capital access, scale, and speed of technological advancement—especially in emerging high-tech sectors like EVs, batteries, AI, robotics, biotechnology, and advanced energy. Europe is fragmented, under-capitalised, and reliant on imported technologies. The Critical Technology Tracker prepared by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) has found China ahead in 57 out of 64 technologies assessed (2019–2023) – up from 3 out of 64 technologies in 2003-2007 dataset. The resulting dilemma for Europe is how to bridge this technology gap.

A key argument gaining traction is the use of technology transfer to access and localise technology in key sectors, whilst avoiding dependence. This article examines the landscape of technology transfer from China and its implications for Europe’s competitiveness, against the wider geopolitical context and Europe’s push towards strategic autonomy.

China leads in 57 out of 64 areas of technology research, as per ASPI (2024)

Key areas where China leads EV components and advanced lithium batteries; Critical raw materials processing technologies; Sustainable industry and green energy technologies; Digital infrastructure, AI, IoT, & smart cities systems; Advanced communications systems and quantum computing.

From Printing Press To Peripheral

Europe was once the leader in global innovation. The printing press, the steam engine, and the jet turbine are examples of European inventions that shaped entire epochs. But in the present race for artificial intelligence, advanced semiconductors, batteries, and quantum computing, Europe finds itself increasingly on the periphery.

European countries score impressively in photonics and robotics niches, but lag US and China in most areas.

A recent report by the ASPI Critical Technology Tracker shows how far the scale has shifted: China now leads in 57 of 64 assessed technologies, ranging from hypersonics, and AI, to advanced materials. In most of the remaining technologies assessed, the US leads. European countries score impressively only in photonics and some niches in robotics – but otherwise rank between third and sixth place, closer to mid-sized competitors like South Korea, Japan, or Turkey than to either of the two superpowers.This matters because the control and use of frontier technologies are critical to midterm economic influence while forming the foundations of military capability. The leaders in areas such as AI and clean energy will help to determine the future of global governance, setting standards and shaping the rules of the game in the coming years and decades.

Europe’s Strategic Weakness

Why is Europe behind? Clearly, it is not for a lack of talent. European universities produce outstanding scientists and engineers, while initiatives like Horizon Europe and Gaia-X, demonstrate an ambition to support technology innovation.

The issue is fragmentation and scale. Research funding is divided among 27 nation states each with their own capital markets and fiscal regimes. Pools for venture capital are smaller and less risk-friendly than in Silicon Valley or Shenzhen. Established firms in some industries in Europe often favour incrementalism rather than disruptive innovation, something witnessed most obviously in Europe’s legacy manufacturing and automotive sectors.

Despite areas of strength in Europe – aerospace, pharmaceuticals, advanced manufacturing – companies struggle to scale new breakthroughs to consumer-facing platforms.

The net result is dependency. Europe imports semiconductors from Asia, consumes US cloud services, and sources solar panels and battery technologies from China. Each point of dependency is a potential point of failure. The gas crisis in 2022 showed after only a few months how quickly energy dependence could become weaponised. There are some justifiable concerns that it could happen again with technology.

China: From Copying to Leading

China’s trajectory makes the European dilemma sharper. Once a case in point of copycatting from the West, Beijing is now innovating at the frontier.

The DeepSeek AI model is a fraction of the cost of western models and Chinese researchers now produce more AI papers than any other nation.

China produces over 80% of global solar panels and 74% of EV battery technology

China manufactures over 80% of global solar panels and 74% of EV battery technology, while China’s own EAST fusion reactor has achieved one of the longest sustained plasma on record.

Nearly all global graphite refining and most lithium and cobalt processing takes place in China. China’s manufacturing output is roughly twice that of the United States, allowing diffusion to take place rapidly.

This shift is intentional. Beijing’s concept of “new quality productive forces” reallocates resources to emerging industries where there is currently no leader. Much like how Great Britain exploited steam, and the United States exploited electricity, China is betting on AI, EV batteries, and quantum computing for 21st-century supremacy.

Between Threat and Opportunity

For Europe, China represents both a threat and opportunity. On the one hand, Europe’s climate ambitions and industrial transformation cannot be achieved without Chinese technologies. On the other hand, dependency presents potential strategic risks.

Total decoupling is impossible to achieve. Economically, it would be self-inflicted harm; technologically, it would accentuate Europe’s backwardness; and politically, it would fray Europe’s ties with China. However, unilateral dependence carries the same risks. The challenge for Europe lies in picking a balanced middle road: to strategically engage, but not become entrapped.

The question is whether cooperation with China can be structured to support EU strategic aims

Simultaneously, China’s expanded presence in Europe’s industrial base is now more than hypothetical — it’s evident in the solar fields of Spain and the battery facilities of Hungary. These projects demonstrate how Chinese investment and technologies can help facilitate Europe’s green and digital transitions, but they also highlight the costs of asymmetry. The question is not whether or not Europe can engage China — it has to — but whether the cooperation can be negotiated to support its long-term independence, not detract from it.

Tech Transfer as a Priority for Europe

The EU and UK will need to maintain and develop strategic channels of cooperation with China in a bid to advance key interests. This seems set to involve a more targeted, selective approach to technology relationships.

EU and UK need to maintain strategic cooperation with China, despite geopolitical challenges.

Here a balance must be found between the need for catch-up and the risk of technological dependency. For this reason, there are murmurings in European capitals about the need to ensure future FDI and technology trades are accompanied by technology transfer in areas of key strategic importance to Europe. Through technology transfer, it is expected that European companies would gain access to frontier technologies and know-how that can be harnessed in the creation of new competitive products. It is also anticipated that OEM supply chains can be diversified and in some cases partially repatriated.

Forms of Tech Transfer

Article 101 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) defines technology transfer of proprietary technology from one entity to another, either through direct assignment or licensing. The Treaty encourages most forms of technology transfer, unless in cases where this distorts competition or establishes a market monopoly. The Technology Transfer Block Exemption Regulation (TTBER) provides guidance as to when a licensing of patents, know-how or software is permissible.

IP licensing arrangements

One form of technology transfer involves IP licensing from Chinese producers to European companies. To achieve this, Chinese intellectual property (IP) would be localised and adapted operationally to meet European regulatory and product standards. This might be achieved through a local SPV, jointly owned with a European partner entity. Tech licensing appeals to Chinese producers looking to establish an export market in Europe, as it does not involve ceding ownership of intellectual property.

Joint venture agreements

Joint investment through joint ventures offers a further legal avenue to securing European ownership of technology, enabling the sharing of skills, whilst allowing FDI from China to be securitised. Notable joint ventures have recently been agreed between Chinese and EU firms, and this appears a trend likely to intensify over the coming years. In the 1990s and 2000s, Chinese industrial policy relied heavily on joint ventures with European firms in the automotive, aviation and chemical industries. These joint ventures gave Chinese firms access to world-class know-how, while European partners gained access to China’s scale and demand. Thus, Europe’s status as a laggard has presaged a reversal of roles.

The truth is that tech and knowledge transfer are a precondition for building competitiveness. No latecomer has ever caught up without it. The question for Europe appears to be not whether it should engage, but rather under what conditions and with what guardrails to ensure autonomy and not dependence.

Selective Leverage: Where Europe Gains

If properly designed, EU leaders hope that technology transfer can be used to increase autonomy and competitiveness. This would be prioritised in sectors where collaboration accelerates Europe’s digital and green transitions — while ensuring safeguards against over dependence. Three sectors are most relevant.

Clean Energy and Climate Technology

In 2023, the EU imported approximately €20 billion worth of solar panels from China, while more than 98% of new installations were supplied by Chinese companies such as Trina Solar and LONGi Solar. This demonstrates both the indispensability of Chinese input and the risks of single-source dependence.

As an illustration of both opportunity and risk, consider CATL’s giga-factory in Debrecen, Hungary (€7.3B investment). While the deployment of Chinese battery technology within the EU is encouraging, it locks European OEMs into longer-term dependence on Chinese chemistries. A possible way forward would be to co-develop chemical supply chains with Chinese firms while investing in joint venture chemistries that enable localisation of IP and vertical integration of the manufacturing process.

Industrial AI and Smart Manufacturing

While Europe cannot compete with Silicon Valley in the consumer internet space, it holds advantages in industrial robotics, logistics, and precision engineering. Partnerships with Chinese firms in these areas could generate real productivity gains.

Joint ventures can enable localisation of IP and knowledge sharing

Consider, for example, the CATL–Stellantis joint venture in Zaragoza, Spain (€4.1B, 50 GWh capacity). This arrangement goes beyond a supply agreement: it represents co-development of European EV production capacity built on Chinese LFP expertise. Such ventures show how joint ventures, once primarily a vehicle for China to gain European know-how, are becoming more reciprocal, allowing EU firms access to scale technologies they might not otherwise achieve.

Biotechnology and Health Innovation

Ageing populations are creating rising health burdens in both Europe and China. Joint research on genomics, pharmaceuticals, and medical devices could yield major breakthroughs.

Here, too, lessons can be drawn from other sectors. Just as BMW secured a guaranteed supply of large cylindrical cells through EVE Energy’s recently constructed plant in Debrecen, future biotechnology collaborations could embed Chinese partners within EU production ecosystems — meeting demand for capacity while ensuring GDPR-level safeguards for data and IP.

Smart and Strategic De-Risking

Investment Screening

The EU currently screens sensitive foreign direct investment. Mario Draghi’s competitiveness review emphasised both Europe’s vulnerability to external dependencies and the need for FDI to be assessed strategically. Investments that enhance resilience and local capacity are welcomed, while those that entrench structural dependencies face stricter scrutiny.

Chinese firms are now more willing to license technology and form joint ventures abroad, underlining the growing importance of the EU market. Europe is seeking to use that leverage to prioritise deals that build autonomy, and scrutinise ones that strengthen monopoly.

IP and Data Protection

Existing legal frameworks such as TTBER and GDPR are existing blueprints that frame IP and data protection. These mandate that contracts should be robust on questions of IP ownership, licensing limits, and data localisation. Without such safeguards, Europe risks repeating past episodes where JVs tilted decisively in China’s favour.

The experience of Tesla is illustrative. Reportedly, Tesla’s Berlin factory relies on CATL’s LFP cells, effectively tying production to Chinese supply despite the facility being in Europe. Without contractual protections, Europe may lose more than it gains..

Allied Partnerships

It is understood that Europe cannot stand alone. Collaborating with partners such as the US, Japan, South Korea, and India can provide parallel supply chains, joint R&D, and standard-setting capacity. Nevertheless, commentators warn that Europe must also prepare for divergence from the US, whose priorities will not always align with EU economic interests.

A Diverging World Mindset

Many assume US technological leadership is permanent, or that China’s ascent will inevitably slow. However, neither outcome is certain.

China’s scale, dominance in critical minerals, and coordination between state and industry create a closed-loop cycle of innovation and diffusion. Even if it does not surpass the US outright, China will remain a peer competitor. This means Europe will no longer face a binary choice of alignment with Washington but a multipolar environment demanding greater flexibility.

Therefore, strategic autonomy requires that Europe prepare for scenarios where it diverges from both Washington and Beijing to act on its own terms.

Emerging European Priorities

So, what is Europe doing about this? Some priorities have begun to emerge:

Resource allocation: R&D budgets at the EU and member state levels can be increased, allocating resources to scale startups into global leaders, thus addressing the industrial capability question. There is evidence that this is occurring across the EU, as part of the Regenerate EU programme.

Areas of strategic importance: This is where Japan’s concept of “strategic indispensability” is applicable. It is possible to differentiate strategically important sectors for inward technology transfer — aerospace, life sciences, advanced manufacturing.

Regulatory standards: Rules are one of the main ways Europe’s power and influence is manifested in the technological landscape. Ethics for AI or clean energy regulation, for example. The EU can help shape the governance of technologies where they do not have dominant positions with collaborative relations; however, this should be done by working with allies and using forums with countries from the wider international community.

Moderate engagement with China, focused on selected strategic areas. China should not be approached through a naive interdependent stance. Nor should it be treated, implicitly or explicitly, as totally excluded with no alternatives. Therefore,

Europe should selectively evolve and manage structured engagement with their counterparts in China and in Europe, in clean energy, industrial AI, and biotech, for example; ideally, setting guardrails to create a framework that manages dependency with safety limits and reduced vulnerabilities.

Conclusion

Twice in recent modern history we have experienced an inflection point in international power dynamics, first to Britain, and then to the United States. We are currently witnessing a third inflection point with China.

The question is whether Europe will finally engage, rather than simply sit on the fence. Technology transfers — licensing, joint ventures, co-development — will be at the forefront. If executed correctly, these can help the EU and UK exercise greater autonomy and achieve more competitiveness.

In European policy circles, a middle ground is sought between decoupling and unguarded engagement, in line with the logic of de-risking. Leveraging imports and FDI for technology and skills transfer is one possible path forward, and something slowly gaining traction at the policy level and in the marketplace.

Thus, the real question is not whether Europe will engage with China, but whether it can do so ‘on its own terms’.