The paradigm of European security, as it was known post-WW2, is set to change. The United States, once the bulwark of the NATO-led Western liberal world order, is increasingly seen as pivoting away from Europe. With the war in Ukraine dragging on and a recalibration of US’ strategic priorities all but apparent, European states have begun re-envisioning European security, albeit with European nations taking on much more significant roles. However, considerable obstacles lie strewn on the path to European self-sufficiency in defence. The U.S. remains the predominant military power within the transatlantic alliance. Its nuclear arsenal, logistics, and intelligence capabilities underpin NATO’s effectiveness as a military force. It also outspends the rest of the alliance combined. In absolute terms, NATO’s estimates of defence expenditure in 2023 depict the U.S. spending more than double the rest of the alliance combined. A reduction in American support for the alliance would undoubtedly massively increase the burden of security placed upon other NATO partners.

Europe has begun taking note. Acknowledging the prospect of a changed NATO with increased responsibilities for European nations, Germany’s prospective Chancellor, Friedrich Merz, floated the idea that an independent European defence capability might be necessary. Merz also publicly cast doubt on NATO’s mutual defence commitments and advocated seeking nuclear security guarantees from France and the United Kingdom as opposed to its existing participation in NATO’s nuclear sharing agreement that the American nuclear arsenal underwrites. French President Macron has repeatedly expressed his openness to the idea of a French nuclear umbrella over Europe, as well as his willingness to station French troops in Ukraine after a ceasefire takes place. UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer followed suit and hosted a virtual session of the “coalition of the willing” countries that could possibly take up peacekeeping roles in Ukraine. The European Commission recently released a white paper, highlighting previous European chronic underinvestment in defence and lays out possible solutions to mitigate capability deficiencies and develop Europe’s defence industrial base. A tectonic shift is well underway for European security. In order to understand this shift, it is vital to analyse and understand the extent of European dependence on American military capabilities.

Technical Capabilities

American techno-military capabilities undergird European defence structures. While many European countries have sizable militaries, they lack capabilities that enable them to function as effective fighting forces. Enablers such as logistics, command and control (C2), intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR), air and missile defences, and long-range strike capabilities are crucial for the operation of a modern military force. Within the NATO umbrella, the U.S. is the principal provider of these services for European militaries. While both the U.K. and France have independent strategic arsenals, nuclear deterrence in Europe massively depends upon the presence of U.S. nuclear weapons and supporting capabilities and infrastructure. However, with the U.S. shifting its focus away from Europe, European countries need to increasingly focus on the technical deficiencies that a security alliance like NATO would inherit without the military and strategic predominance that the U.S. brings to the table.

Figure 1. Comparison of nuclear arsenals of United States, United Kingdom, Russia, and France.

In the realm of nuclear deterrence, certain German political elites have been voicing support for French and British nuclear guarantees in a bid to attain strategic independence from the U.S.. French President Macron has referred to French vital interests as having a European dimension, implicitly proposing a renewed role for French nuclear weapons in ensuring European security. However, the French nuclear arsenal, consisting of around 300 nuclear warheads, is quantitatively weaker than that of the U.S. with its approximately 5,000 warheads and that of Russia with its over 5,500 warheads, and is thus unlikely to offer the same level of deterrence. Moreover, French nuclear doctrine places the nuclear prerogative solely with the French President, unlike NATO’s Nuclear Planning Group (NPG), which allows all NATO countries, except France, to consult on and review the alliance’s nuclear policy. The British nuclear arsenal, comprising around 225 warheads, is quantitatively and qualitatively limited with US-supplied submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) as its sole nuclear delivery vehicles, something which casts doubt on its credibility and independence. Furthermore, disarmament advocates argue that stationing British or French nuclear weapons in a non-nuclear weapon state like Germany would violate at least the spirit, if not the letter, of the Non-Proliferation Treaty, and be incongruent with British and French disarmament obligations.

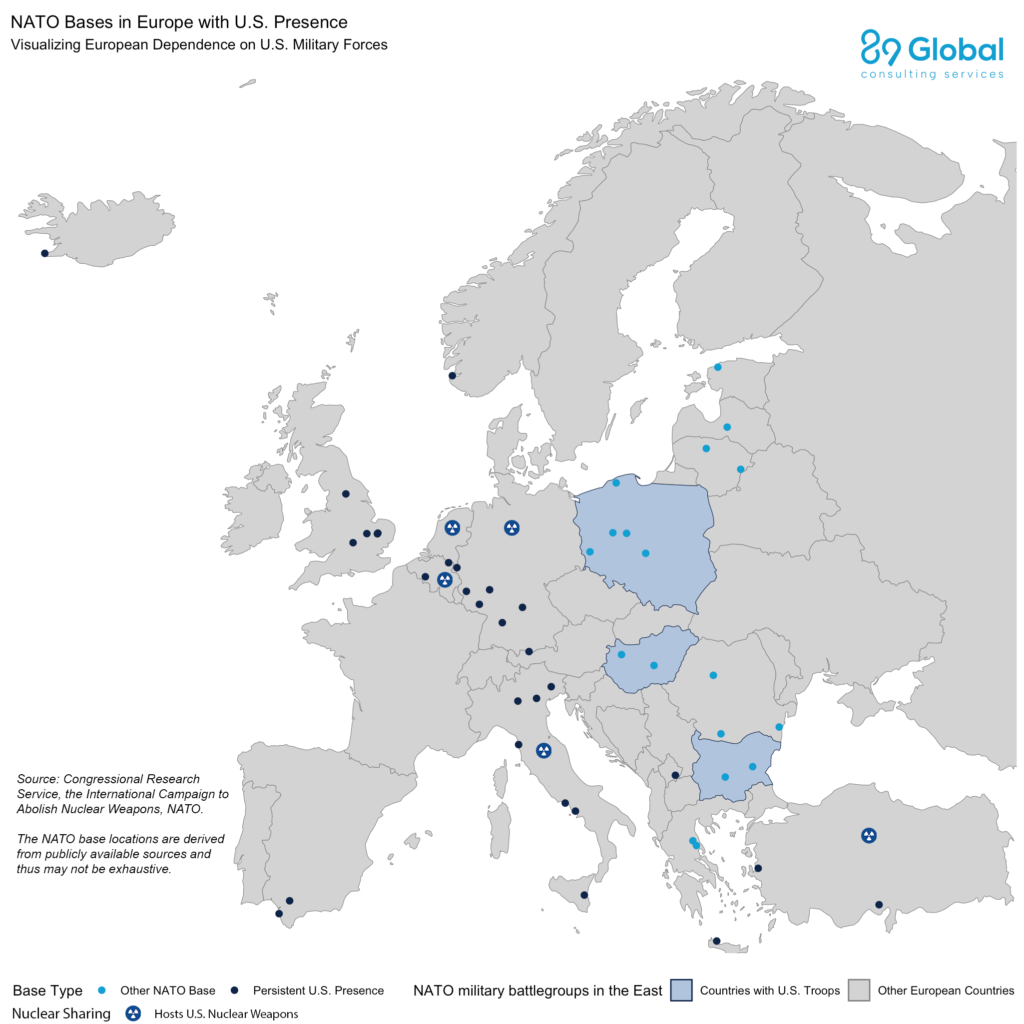

The U.S. plays a significant role in conventional security, deploying thousands of American troops in forward deployment positions and bases throughout Europe. In a 2024 commentary, the Center for Strategic and International Studies posited that Europe’s most significant security need lies in the conventional domain. European security forces are underfunded and under-equipped to deter a militarily resurgent Russia. American Defence Secretary Pete Hegseth has already put Europe on notice by stating that the American military presence in Europe should not be taken for granted and that Europe should take more responsibility for its security. In a joint publication with the Kiel Institute for World Economy, Bruegel, a European think-tank, estimated that Europe would need to raise a fighting capacity equivalent to 300,000 troops, or approximately 50 brigades, to ensure conventional deterrence against Russia. These conventional capabilities would also be needed to provide peacekeeping forces in Ukraine, in the event of a European security guarantee.

Figure 2. Map depicting NATO strategic presence in Europe.

A European force would be ineffectual without generating critical capabilities, such as ISR, long-range strike capabilities, and air defences. It currently depends on the U.S. for several such capabilities. The Centre for European Policy Analysis pointed out in a recent article that while European militaries are well-trained, their lack of critical capabilities undercuts their ability to sustain military operations during conflict. The 2023 EU Capability Development Plan highlighted 22 capabilities Europe needs to invest in to address operational realities and future challenges. Europe’s lack of unified command and defence forces further complicates its ability to function cohesively and effectively project deterrence. The EU Commission’s White Paper on European Defence Readiness 2030 captures these capability shortfalls in terms of seven priority areas that are critical for an effective EU defence, proposing collaborative frameworks to close those capability gaps efficiently. It also highlights the impediments to military mobility and a lack of transport infrastructure in Europe and promises to put forward a joint EU communication on ameliorating the situation within this year.

Figure 3. Map depicting number of American troops in NATO countries in Europe.

Financial Expectations

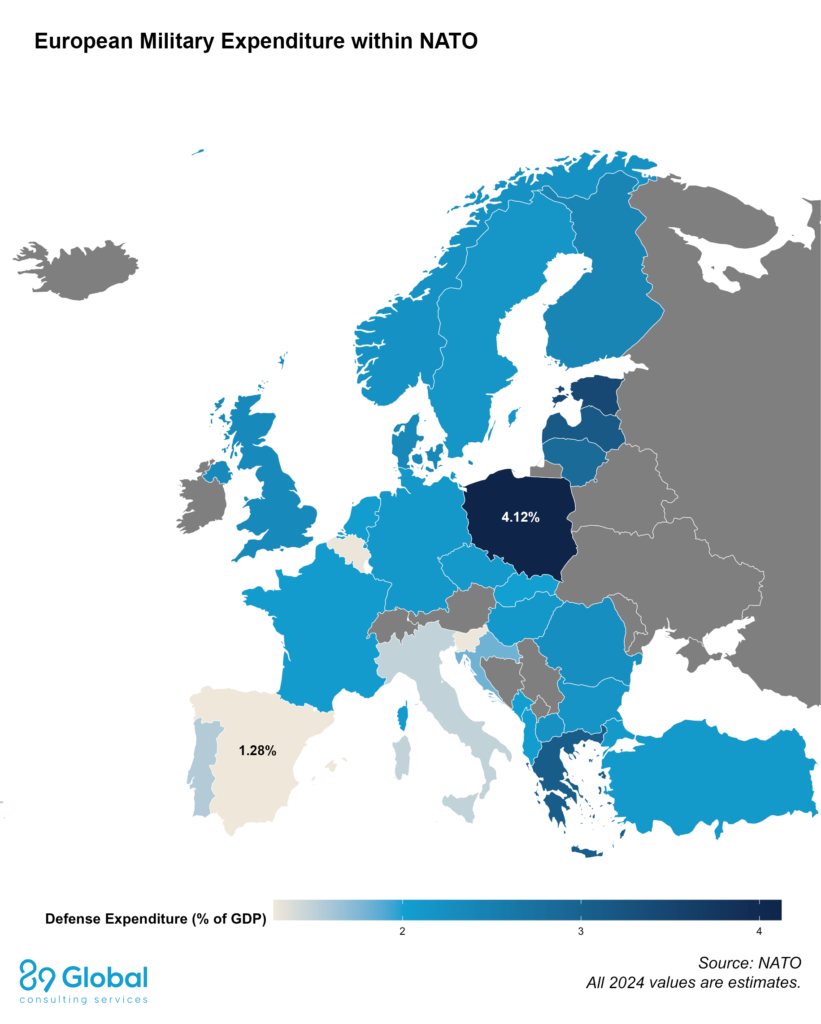

Europe is increasingly acknowledging the need to ramp up defence spending in the wake of the U.S. reenvisioning its strategic priorities. With the exception of Hungary’s Victor Orban, European leaders reiterated their support for Ukraine and backed plans to increase their defence spending at the recent EU defence summit held on the 6th of March in Brussels. Bruegel estimates that European defence spending will have to increase by around €250 billion annually in the short term to meet its security needs. The European Commission presented an €800 billion plan that would allow member states to increase their defence expenditures significantly. This includes relaxing the EU’s fiscal rules, providing €150 billion of loans for defence investment, using the EU budget to direct greater funding towards defence-related investments, and mobilising private capital through the European Investment Bank and by accelerating the Savings and Investment Union initiative.

Figure 4. Map depicting defense expenditure as a percent of GDP of NATO countries.

National governments are also enacting steps to increase their military capabilities. In Germany, the CDU-CSU and the SPD, who will likely form the next German federal government, have agreed to reform the country’s constitutional fiscal borrowing rules to allow for more significant defence expenditure. The U.K.’s Prime Minister, Keir Starmer, has committed to increase defence expenditure to 2.5% of the GDP from 2027, with a goal to reach 3% in the next parliament. French President Macron voiced support for European countries to increase their defence expenditure to “around 3-3.5%.” NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte has encouraged countries to spend more than 3%. However, only 24 of the 32 NATO allies spend 2% of their GDP on defence. The U.S. has, however, called for NATO countries to spend as much as 5% of their GDP on defence, a demand rejected as unfeasible by some. Others have recently cast doubt on the collective security principle at the heart of the alliance by equivocating on Washington’s willingness to defend allies that do not spend enough.

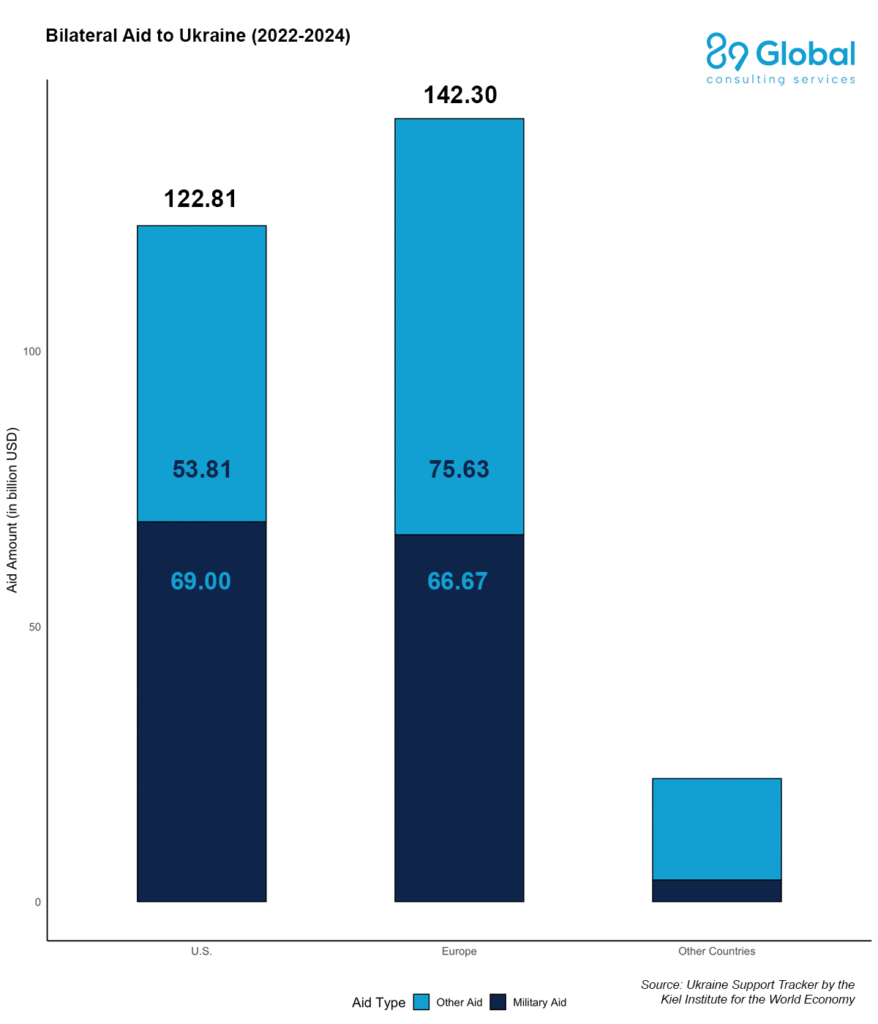

In an attempt to pressure Kyiv to agree to enter negotiations with the Russians, the U.S. briefly suspended military aid to Ukraine*, a move that halted roughly €1 billion worth of arms. According to the Kiel Institute for World Economy’s The Ukraine Support Tracker, Europe has provided €142.3 billion in aid from 2022 to 2024 while the U.S. has provided €122.81 billion. However, the U.S. is still Ukraine’s biggest supporter in terms of military aid, having sent €69 billion and provided weapon systems like High Mobility Artillery Mobility System (HIMARS), Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS), Patriot Air Defense systems, M1A2 Abrams tanks, Bradley infantry fighting vehicle, M777 howitzer, etc. The suspension of U.S. intelligence sharing with Ukraine highlighted Europe’s inability to provide similar capabilities and is an example of some of the inadequacies of European military assistance to Ukraine. In a recent news report, the media outlet Vox highlighted that apart from a lack of equivalent European systems that could be substituted for American military equipment, European countries also lack enough military stockpiles to provide substantial aid to Ukraine. Moreover, with rising calls for European rearmament in the air, keeping Ukraine supplied with military equipment might be a competing priority. In a similar vein, Politico reported that at the recent European defence summit in the wake of the suspension of American military assistance, European leaders focused more on ramping up the bloc’s own defence rather than covering Ukraine.

*The U.S. has since then resumed military assistance and intelligence sharing.

Figure 5. Graph depicting a breakdown of bilateral aid to Ukraine,

Outlook

In recent years, European security has been increasingly challenged. War is once again near its border, traditional alliances have been questioned, and coupled with the advent of disruptive technologies, the once-thought-to-be unshakeable assumptions that undergird Pax Europa can no longer be deemed secure. In this new age of European security, Europe is striving to recover a much more active role in its own security. European countries need to spend more, increase capabilities and troop numbers, expand their defence industrial base, and be ready to project deterrence. However, a move in this direction is fraught with numerous pitfalls that could endanger Europe’s quest for greater security and strategic autonomy.

Fears of an American pivot away from Europe have led European governments and intergovernmental institutions to examine the deficiencies in their defence capabilities. However, Europe’s dependence upon American military and nuclear defence cannot be reversed in the short term. While certain European elites have been publicly pondering whether the French or British nuclear capabilities could substitute the American nuclear umbrella, the wide qualitative and quantitative disparity between the American and European nuclear arsenals undermines the feasibility of such a switch. Moreover, while recent rhetoric might have undermined U.S. willingness to come to the aid of NATO partners who don’t spend enough, it has not hinted at removing its nuclear shield over Europe. However, French nuclear forces could serve as a complement to NATO, integrating its nuclear planning with NATO and enabling European countries to take greater responsibility for their strategic security.

Europe’s capability deficiencies have also been thrown into sharp relief in recent months as European leaders grapple with the reality of oversized dependence on American capabilities. While reforms are much needed in order to close these capability gaps, the most critical resource in catching up is time. It will take years for Europe to be in a position to overcome its deference to the U.S.. In the short term, Europe needs to ensure that it forges the political will and financial wherewithal necessary in order to ensure European security and defence in a rapidly changing global environment.